Journal of Cancer Research & Therapy

An International Peer-Reviewed Open Access Journal

ISSN 2052-4994

- Download PDF

- |

- Download Citation

- |

- Email a Colleague

- |

- Share:

-

- Tweet

-

Journal of Cancer Research & Therapy

Volume 6, Issue 5, September 2018, Pages 32–36

Short reportOpen Access

Characterizing tobacco use in an American cancer center’s catchment area can help direct future research priorities

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, 3535 Market Street, Suite 4100, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

- 2 School of Medicine and Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, 801 Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

*Corresponding author: Robert Schnoll, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, 3535 Market Street, 4th Floor, Philadelphia, PA, 19104. Tel.: 215-746-7143; E-mail: schnoll@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Received 26 June 2018 Revised 03 August 2018 Accepted 15 August 2018 Published 23 August 2018

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14312/2052-4994.2018-5

Copyright: © 2018 Schnoll R, et al. Published by NobleResearch Publishers. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

AbstractTop

Purpose: American cancer centers supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) must ensure that their research addresses the cancer relevant needs and risks of members of their catchment area. In 2016, the NCI supported catchment area assessments. This is the first study to describe a cancer center catchment area cancer risk evaluation, focusing on tobacco use and lung cancer screening. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted in 2017 with 1,005 residents within a Philadelphia cancer center catchment area to identify the rate and correlates of smoking and rate of lung cancer screening. Results: The rate of current smoking in the catchment was 13%. Current smokers were more likely to have depression/anxiety, less likely to be eating healthy, more likely to use e-cigarettes, and endorsed lower perceived health and higher cancer fatalism, vs. former (27%) or never smokers; 74% of smokers want to quit smoking, but two-thirds think nicotine dependence medications are unsafe and ineffective, which may be addressed with personalized treatment. E-cigarette use was 11% and lung screening rates were < 30%. Conclusions: These results indicate that addressing tobacco use in the cancer center’s catchment may require targeting comorbid psychiatric conditions and additional cancer risk behaviors such as poor diet, modifying cancer beliefs that may undermine cessation, and utilizing novel methods to promote utilization of evidence-based treatment for smoking. E-cigarette use should be targeted, as well as identifying methods to promote lung screening. This study shows how a cancer center can identify catchment area needs to plan research that reduces the burden of cancer among their residents.

Keywords: smoking; lung cancer screening; catchment area

IntroductionTop

Across the United States, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) supports more than 60 cancer centers, which provide clinical care and lead the nation’s research effort to reduce the burden of cancer in the US. In 2016, the NCI required that each cancer center maintain a commitment to ensuring that their research portfolio addresses the specific risk factors that are prevalent among members of their catchment area. To support cancer centers in this effort, the NCI provided Administrative Supplement funding to cancer center support grants to describe catchment area resident’s cancer risks and guide future research [1].

Tobacco use is a leading risk factor for cancer and remains prevalent in the US and elsewhere around the globe. Smoking is causally linked to many cancers, including lung and head and neck cancer [2], and upwards of 15% of Americans continue to use tobacco daily [3]. Despite substantial progress in the US to reduce the rate of smoking, novel initiatives are needed to continue to effectively reduce the rate of smoking across the nation and serve as effective models for eradicating tobacco use around the globe.

The present study describes, for the first time, the results from a cancer center catchment area assessment led by a University-based cancer center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which is a large urban cancer center located in the Northeast part of the US. The present analyses and report focuses on tobacco use data collected as part of this assessment, correlates of tobacco use, including beliefs, psychiatric comorbidity, and health behaviors, e-cigarette use, use of medications for tobacco dependence, and lung cancer screening rates. The results from this catchment area assessment were designed to offer directions for future catchment area research that specifically meets the needs of catchment area residents.

Materials and methodsTop

This cross-sectional survey was conducted in January 2017 by the Public Health Management Corporation (PHMC), which implements biennial surveys in the Philadelphia region using both land-line and cell-phones. Respondents were a random sample of adults, 18-75 years of age (English- or Spanish-speaking), who had completed the 2015 Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey (n = 10,048). Respondents were selected, using random-digit dialing and the “last birthday” method, from Philadelphia and 5 neighboring counties, which account for > 54% of University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center (ACC) patients (response rate = 44.4%). PHMC ascertained informed consent and methods were approved by the Penn Institutional Review Board. These counties were selected since they have higher proportions of minority and economically-disadvantaged communities within ACC’s catchment; 1,005 respondents completed the survey, which included items from established surveys (e.g., Health Information National Trends (HINTS) [4]): demographics; health status and access to care; cancer screening; risk perceptions; and behaviors (e.g., smoking, e-cigarette use). Respondents indicated the number of times each day they eat fruit and vegetables, daily soda intake (1 = > once/day to 5 = 0 times this month), weekly exercise (1 = never to 4 = 3 times or more per week), perceived cancer risk (1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely) and perceived health (1 = excellent to 5 = poor), and cancer relevant attitudes (e.g., everything causes cancer; 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree).

The survey was supplemented with questions regarding the use of medications to quit smoking and whether the use of a blood test to personalize the selection of quit smoking medications in order to improve effectiveness and safety would affect willingness to use quit smoking cessation medications [5].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and bivariate statistics (e.g., ANOVA, chi-square) characterized the sample and differences between current, former, and never smokers.

ResultsTop

The rate of current smoking was 13% and 27% were former smokers (Table 1). Gender and race were not associated with smoking, but age and household income were, with more current smokers reporting that they find it difficult or very difficult to get by on their household’s income, vs. former and never smokers. Smokers were also significantly more likely to live in zip code areas with lower median incomes and were less likely to have health insurance, vs. former and never smokers. Current smokers reported higher rates of lung disease and depression or anxiety, vs. former and never smokers. Current smokers reported significantly lower Body mass index (BMI) and daily soda intake, but lower daily fruit and vegetable consumption and weekly exercise, and greater weekly fast food consumption, vs. former and never smokers.

| Characteristic | Current (N = 133) N (%) or M (SD) |

Former (N = 271) N (%) or M (SD) |

Never (N = 601) N (%) or M (SD) |

Overall (N = 1005) N (%) or M (SD) |

F or χ2 | p | |

| Sex | 3.2 | 0.2 | |||||

| Male | 53 (40) | 124 (46) | 237 (39) | 414 (41) | |||

| Female | 80 (60) | 147 (54) | 364 (61) | 591 (59) | |||

| Race | 4.9 | 0.3 | |||||

| White | 87 (67) | 201 (76) | 441 (76) | 729 (75) | |||

| Black | 34 (26) | 54 (20) | 108 (19) | 196 (20) | |||

| Other | 8 (6) | 11 (4) | 31 (5) | 50 (5) | |||

| Age | 55.6 (11.0)a | 58.5 (10.7)b | 52.4 (12.0)c | 54.5 (11.8) | 26.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Income | 40.5 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Comfortable | 34 (26) | 129 (48) | 310 (52) | 473 (47) | |||

| Getting By | 62 (16) | 100 (37) | 228 (38) | 390 (39) | |||

| Difficulty | 36 (27) | 41 (15) | 61 (10) | 138 (14) | |||

| Zip code income* | $51,674 | $67,318 | $70,119 | $66,899 | 21 | < 0.001 | |

| Health insurance | 6.1 | 0.05 | |||||

| Yes | 125 (95) | 268 (99) | 579 (96) | 972 (97) | |||

| No | 6 (5) | 3 (1) | 22 (4) | 31 (3) | |||

| Medical visits past year | 4.5 (6.8) | 4.4 (5.6) | 3.8 (6.3) | 4.1 (6.2) | 1.1 | 0.35 | |

| BMI | 27.8 (5.5)a | 30.0 (7.2)b | 28.7 (6.4)b | 29 | 5.7 | 0.004 | |

| Lung disease | 19.8 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 13 (10) | 18 (7) | 12 (2) | 43 (4) | |||

| No | 120 (90) | 253 (93) | 587 (98) | 960 (96) | |||

| Depression or Anxiety | 7.3 | 0.03 | |||||

| Yes | 37 (28) | 63 (23) | 109 (18) | 209 (21) | |||

| No | 96 (72) | 208 (77) | 492 (82) | 796 (79) | |||

| Personal cancer | 2.7 | 0.26 | |||||

| Yes | 16 (12) | 39 (14) | 63 (11) | 118 (12) | |||

| No | 117 (88) | 232 (86) | 537 (89) | 886 (88) | |||

| Family cancer | 5.2 | 0.08 | |||||

| Yes | 79 (60) | 160 (59) | 312 (52) | 551 (55) | |||

| No | 52 (40) | 110 (41) | 284 (48) | 446 (45) | |||

| Cannot afford doctor | 0.94 | 0.62 | |||||

| Yes | 11 (8) | 20 (7) | 37 (6) | 68 (7) | |||

| No | 122 (92) | 251 (93) | 562 (94) | 935 (93) | |||

| Daily fruit & vegetables | 2.4 (1.7)a | 3.0 (1.8)b | 3.1 (2.0)b | 3.0 (1.9) | 8.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Daily soda | 3.8 (1.3)a | 4.2 (1.0)b | 4.2 (1.0)b | 4.1 (1.1) | 8.3 | < 0.001 | |

| Weekly fast food | 0.89 (1.7)a | 0.50 (0.99)b | 0.59 (0.91)b | 0.60 (1.1) | 6.3 | 0.002 | |

| Weekly exercise | 3.0 (1.1)a | 3.2 (1.0)b | 3.3 (1.0)b | 3.2 (1.0) | 4.2 | 0.02 | |

| Ever used e-cigarette | 219.7 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 73 (55) | 25 (9) | 14 (2) | 112 (11) | |||

| No | 60 (45) | 246 (91) | 587 (98) | 893 (89) | |||

| Current e-cigarette use | 4.7 | 0.1 | |||||

| Yes | 11 (15) | 8 (32) | 1 (7) | 20 (18) | |||

| No | 62 (85) | 17 (68) | 13 (93) | 92 (82) | |||

| Perceived cancer risk | 3.2 (1.1)a | 2.8 (1.2)b | 2.7 (1.1)b | 2.8 (1.1) | 12.7 | < 0.001 | |

| Everything causes cancer | 2.7 (1.4)a | 3.0 (1.3)b | 3.1 (1.2)b | 3.0 (1.3) | 6.6 | 0.001 | |

| Not much can be done to lower cancer risk | 3.1 (1.5)a | 3.7 (1.3)b | 3.8 (1.3)b | 3.7 (1.3) | 16.6 | < 0.001 | |

| Hard to know which cancer prevention advice to follow | 2.2 (1.4)a | 2.6 (1.3)b | 2.6 (1.3)b | 2.5 (1.3) | 5.6 | 0.004 | |

| Thinking about cancer, I think about death | 2.9 (1.7)a | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.2 (1.5)b | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.2 | 0.04 | |

| Perceived health | 2.8 (1.1)a | 2.6 (1.1)a | 2.3 (1.0)b | 2.5 (1.1) | 17.5 | < 0.001 | |

Note: Superscript letters that are different represent statistically significant differences based on Tukey’s HSD. * indicates median instead of mean.

Overall, 11% of the sample indicated ever using an e-cigarette. More than half of current smokers reported ever using an e-cigarette, which was significantly greater than former and never smokers. Among those who have ever used an e-cigarette, the rate of current e-cigarette use was 15%, 32%, and 7%, across current, former, and never smokers (p = 0.10), respectively.

Current smokers perceived their health as worse than former or never smokers and perceived greater personal cancer risk. Current smokers, vs. former and never smokers, more strongly believed that “everything causes cancer”, “there’s not much you can do to lower your chances of getting cancer”, “there are so many different recommendations about preventing cancer, it’s hard to know which ones to follow”, and “when I think about cancer, I automatically think about death”.

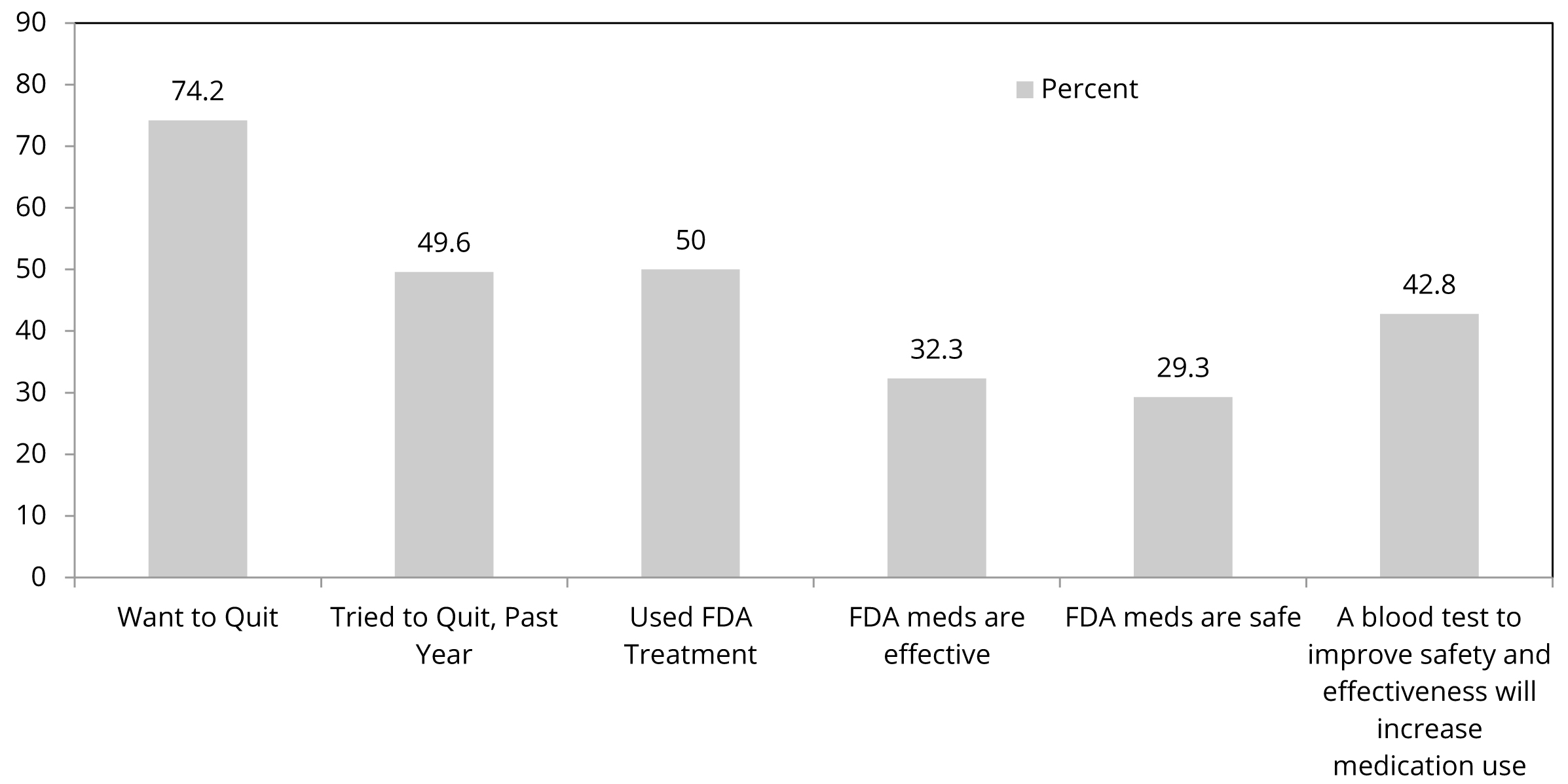

Almost three-quarters of current smokers indicated they want to quit smoking, half of them have made a quit attempt in the past year, and half who have tried to quit smoking have used a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) medication (nicotine replacement therapy; bupropion; varenicline) to do so (Figure 1). However, two-thirds of current smokers think FDA-approved nicotine dependence medications are ineffective and unsafe. These beliefs were associated with lower past medication use. However, importantly, 43% of all current smokers indicated that, if a blood test could personalize medications to increase efficacy and safety, they would be willing to use a medication. A slightly greater proportion (45%) of current smokers who have never used an FDA medication in a quit attempt indicated would do so with personalized treatment recommendations.

Abbreviations: PHS: Public Health Service; FDA: Food and Drug Administration.

For those age 55 or older (N = 521), which is the current age cut-off for lung cancer screening), 25% of current and 15% of former smokers reported having spoken with a healthcare professional about lung cancer screening and 29% of current and 17% of former smokers reported having undergone lung CT screening. Rates of speaking with a healthcare professional and rates of lung cancer screening were significantly higher among current, vs. former smokers (p > 0.05); 6% of current smokers and 5% of former smokers spoke with a healthcare professional but did not get screened and the likelihood of screening was strongly associated with speaking with a healthcare professional about screening for both current and former smokers.

We examined if personal or family history of cancer modified any of these results. Consideration of a personal cancer history did not affect the results described above, but a family history of cancer interacted with smoking status with regard to perceived health (p = 0.021) and soda consumption (p = 0.03). Current smokers with a family history of cancer had worse perceived health and current smokers without a family history of cancer consumed the least amount of soda.

DiscussionTop

This study evaluated tobacco use in a catchment area of a Philadelphia cancer center, a large area in the Northeast of the United States, and examined correlates of, and issues related to, tobacco use in order to guide future research by the cancer center that directly addresses the needs of catchment area residents.

First, the smoking rate in this catchment area was lower than the national average of 15.1% [3]. This may have been due to our survey including ∼50% of respondents from high median household income counties (e.g., Bucks [$76,824]; Chester [$84,741], and Montgomery [$76,380]), vs. Philadelphia ($41,233), which is unlike past surveys that documented higher smoking rates in this region [6]. Nevertheless, over 13% of adult residents in this catchment are current smokers, indicating that addressing tobacco use remains a priority for this cancer center. Former smokers were older than never and current smokers, which may reflect that a greater recognition of the adverse health effects that comes with age, underlies this result. Further, current smokers had lower BMIs, which can reflect the effects of nicotine on food metabolism. But, BMI was associated with greater fast food intake for former and never smokers and not current smokers, which suggests that this relationship may be attributable to different behaviors as well.

Second, additional results from this analysis highlight potential catchment area research priorities focused on reducing tobacco use. The present data suggest that future efforts to address smoking in this catchment area should consider the social determinants of health risk behaviors (as reflected in the relationship between smoking status and personal and neighborhood income), comorbid psychiatric disorders [7], multiple cancer risk behaviors [8], cognitions that undermine cessation [9], and risk for post-cessation weight gain [10]. Additional research is needed, perhaps using prospective designs, to validate these factors as potential intervention targets in order to enhance intervention effectiveness. Further, the present data support recent calls for research to address the low utilization of FDA-approved smoking cessation medications among smokers attempting to quit [11]. The present data suggest that personalizing treatment selection by using a biomarker that can improve treatment effectiveness and safety may increase medication use (e.g., [12]). Future prospective studies could test if translating this biomarker into clinical practice (e.g., into primary care) actually increases utilization of evidence-based care and results in substantial decreases to current smoking rates.

Third, our data show e-cigarette use to be a significant public health issue in this catchment. Although we did not specifically ask about dual use or product switching and our numbers are small, our data show that 13% of the sample have lifetime use of e-cigarettes, 8% of current combustible smokers use e-cigarettes (dual use), and 3% of former combustible tobacco users currently use e-cigarettes (switching). However, while e-cigarette use is increasing around the US, there is a paucity of scientific evidence that shows that e-cigarettes can be used to effectively quit smoking and whether or not they are safe [13]. A priority for this catchment area, therefore, should be to develop and disseminate appropriate health messages concerning the efficacy and safety of e-cigarettes as a method for reducing or eliminating combustible tobacco use.

Lastly, our data underscore the need for studies to identify methods to promote lung cancer screening. Lung cancer CT screening is an effective method for the early detection of lung cancer [14]; however, utilization rates remain very low. Smokers are more likely to have lung disease but lung screening rates in the present catchment area are < 30% for current and former smokers. Those with lower perceived risk in this study were less likely to be screened suggesting that perceived risk vs. relative risk is influencing screening decision-making. In addition, few smokers have spoken with a healthcare professional about lung cancer screening, which suggests that future studies could evaluate more effective methods for promoting patient-clinician communication about lung cancer screening to increase utilization of this early detection technology.

Limitations

These findings should be considered in the context of study limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional and, thus, no causal inferences are possible from the results. Second, the data were self-reported and, for certain variables, such as smoking, this may result in under-reporting of cancer relevant risk factors. For other variables, such as attitudes about cancer, we can only speculate about whether or not their self-reports manifest behaviorally. Also, since this was an exploratory study, we did not control for multiple comparisons. Lastly, the response rate of 44%, albeit acceptable for a survey study such as this, may limit the representativeness of the sample and restrict generalization of the results to other populations.

ConclusionTop

Despite these limitations, the present results show how NCI’s supplement to cancer centers around the US can help characterize important features concerning smoking behavior among residents in a catchment area which, in turn, can guide future research initiatives to reduce the burden of cancer in a catchment area. In particular, the present study indicates that, to address smoking in this catchment area, researchers at this cancer center could consider studies that test interventions that also address the social determinants of health, and comorbid psychiatric conditions and other cancer risk factors such as poor diet, and evaluate interventions that address e-cigarette use and low rates of lung cancer screening. Cancer centers can play an important role in improving catchment area resident quality of life through smoking cessation efforts among cancer patients [15] and may be able to do so in their catchment area more broadly as well. In these ways, the specific tobacco-related issues within the cancer center’s catchment area may be addressed in order to reduce overall cancer risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Vicky Tam, M.A., from the University of Pennsylvania Cartographic Modeling Lab, for assistance with the analyses.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by an Administrative Supplement from the National Cancer Institute to grant P30 CA16520-40S3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ReferencesTop

[1]Population health assessment in cancer center catchment areas. National Cancer Institute.Article

[2]National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The health consequences of smoking—50 Years of Progress: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014.Article Pubmed

[3]Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, et al. Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016; 65(44):1205–1211.Article Pubmed

[4]National Cancer Institute,Health Information National Trends Survey. Article

[5]Shields AE, Levy DE, Blumenthal D, Currivan D, McGinn-Shapiro M, et al. Primary care physicians' willingness to offer a new genetic test to tailor smoking treatment, according to test characteristics. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008; 10(6):1037–1045.Article Pubmed

[6]A report from The Pew Charitable Trusts. Philadelphia 2017. Article

[7]Hitsman B, Papandonatos GD, McChargue DE, DeMott A, Herrera MJ, et al. Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction. 2013; 108(2):294–306.Article Pubmed

[8]Green AC, Hayman, LL, Cooley, ME. Multiple health behavior change in adults with or at risk for cancer: A systematic review. Am J Health Behav. 2015; 39(3):380–394.Article Pubmed

[9]Niederdeppe J, Levy AG. Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention and three prevention behaviors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007; 16(5):998–1003.Article Pubmed

[10]Bush T, Lovejoy, JC, Deprey M, Carpenter KM. The effect of tobacco cessation on weight gain, obesity, and diabetes risk. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016; 24(9):1834–1841.Article Pubmed

[11]Ku L, Bruen BK, Steinmetz E, Bysshe T. Medicaid tobacco cessation: Big gaps remain in efforts to get smokers to quit. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016; 35(1):62–70.Article Pubmed

[12]Lerman C, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW, Cinciripini P, George TP, et al. Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015; 3(2):131–138.Article Pubmed

[13]Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, Abudayyeh H, Niaura RS, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: A systematic review. Am Prev Med. 2017; 52(2):33–66.Article Pubmed

[14]Prosch H. Implementation of lung cancer screening: Promises and hurdles. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2014; 3(5):286–290.Article Pubmed

[15]Andreas S, Rittmeyer A, Hinterthaner M, Huber RM. Smoking cessation in lung cancer-achievable and effective. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013; 110(43):719–724.Article Pubmed